| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 |

Originally published on the Extra Life Community website

Edited by Jack Gardner

Fans and critics of Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children alike have commonly perceived it as lacking a compelling story, complex characters, and purposeful fight scenes. When I decided I wanted to understand why I still loved the film in 2013, I didn’t expect the answer I found. The previous articles in this series debunked these major criticisms of the film by examining what story Advent Children tells and how it tells that story through action. This leaves the question, why did it take twelve years to notice that this film portrays the opposite of what everyone says about it? If these criticisms don’t have merit, or are at most overexaggerated, how did they originate? The dominantly negative reviews about Advent Children appear to spawn from its subtle and unconventional storytelling combined with misconceptions that it doesn’t have a meaningful story to begin with.

Advent Children frequently uses visual language, thematic imagery, and minimalist storytelling to convey its story and ideas. Movies communicate their stories visually through shot composition, lighting, costuming, video editing, and positioning of props and actors. These elements are called the film’s mise-en-scène. While films can also use verbal, written, and musical language to convey meaning, film theorists claim that as a visual medium, movies should tell their stories visually. Characters should speak less and do more. As a subscriber to this theory, Advent Children doesn’t always tell the audience what’s happening and what it means through dialog; it shows them through its mise-en-scène.

Sometimes Advent Children’s scenes seem more representative of the film’s themes and ideas than of what is actually happening. For example, the final scene in the movie where we see Cloud surrounded by orphans, townspeople, and friends, both dead and alive, after crashing through the roof of a church is ridiculous even in the world of Advent Children. This scene, however, represents Cloud’s reunion with his friends, his family, and the world. He has found happiness and is ready to accept life over his memories and thoughts of death. In an earlier scene, Cloud also finds himself in an equally ridiculous scenario. Menacing orphans surround him while Kadaj taunts him. It doesn’t make sense that orphans pose a threat to a superhuman like Cloud, but they represent his separation from the world and heighten the tone of helplessness in the scene. By isolating himself, Cloud’s made enemies out of the people he cares about in addition to having to fight his actual enemies and demons.

In general, Advent Children takes a minimalist approach to storytelling. It doesn’t repeat spoken information often. The film explains Jenova, Sephiroth, and materia only once, for example. It encourages viewing the film multiple times as opposed to spoon-feeding an obvious tale that viewers can see once and completely understand. While the film shows us all the information we need to understand the story, it doesn’t always put it together. The characters don’t have extensive conversations to analyze the pieces and find meaning in the outcomes.

These storytelling methods as used by Advent Children and other artworks rely to some degree on the viewer’s analytic skills and personal experiences, which has strengths and weaknesses. Advent Children gives the audience the respect and space to put its clues together themselves and incorporate their own experiences with Final Fantasy VII and real life into the film. This allows viewers to create their own powerful connections to the work either because it reminds them of personal experiences or because finding meaning in it takes effort and feels rewarding. Minimal storytelling, however, also opens the possibility that viewers will interpret the work in unintended ways. For example, audiences can interpret Advent Children’s narrative as meaningless nonsense. Viewers also may not be able to find intended meanings in the work because they don’t have the required experiences. Someone who’s never played Final Fantasy VII, for example, won’t see the similarity between Kadaj’s relationship with Cloud and Cloud’s relationship with Sephiroth. Someone unfamiliar with mental illness might not see it in Advent Children or might interpret Cloud’s character as clichéd. This doesn’t mean, however, that they can’t find meaning in the work through other experiences and clues from the film. Telling a story in this way can also make it impenetrable for casual viewers. Advent Children has plenty of action and fan service at its surface, but it takes work to see that it’s not just mindless entertainment.

Advent Children also has some specific problems that make recognizing that it has meaning difficult. Its purely thematic imagery, for example, creates plot holes that can’t be filled so easily. The director’s cut Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children Complete attempts to explain why the children and townspeople gather at the church at the end of the movie with an event even more ridiculous than the scene itself. Aerith, a dead woman, calls everyone on their cellphones, even the orphans, and tells them to go to the church… Similarly, Cloud’s apparent isolation in the final fight scene continues one of the film’s visual themes but doesn’t make sense in the story’s world, considering that his friends would never leave him to fight a worldwide threat on his own. Sometimes Advent Children withholds too much information as well. To a point, the director’s cut better explains Denzel and how he befriended Cloud, a character that struggles to display and accept affection.

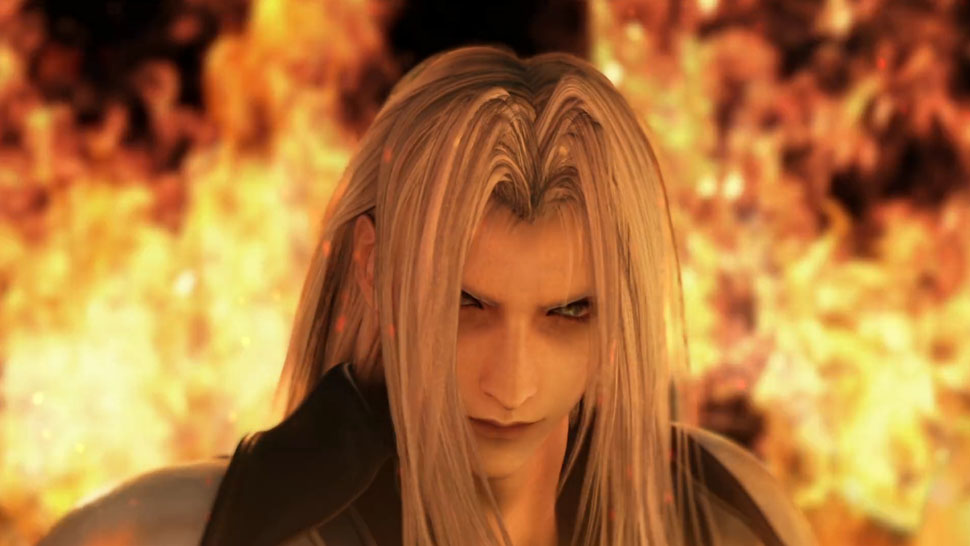

Viewers can easily miss this visual and minimalist storytelling, especially if they have preconceptions that the work doesn’t contain meaning. Unfortunately, Advent Children has an association with three types of movies known for poor storytelling: fan service films, photorealistic CGI, and video game movies. Reviewers say that Advent Children is obviously a “fan service film.” This term has two meanings, depending on the reviewer using it. First, these films tell a story that only fans will understand and appreciate. Second, fan service films have a bad story that exists only to show fans what they want to see, most often battles between characters from the base material. This labeling suggests that people who haven’t played Final Fantasy VII before shouldn’t even attempt to find meaning in Advent Children. At the same time, fans of the game claim that Advent Children can’t contain a good story because it sequels an already complete one. It doesn’t have any more story to tell. They also claim that it exists only to sell Final Fantasy VII merchandise such as the Crisis Core and Dirge of Cerberus video games, which came out at about the same time. Therefore, it’s meaningless fan service and merchandising.

Critics don’t provide enough evidence that Advent Children is any of these things though, and it’s really not obvious. Some people, like myself, watch the film with little to no experience with Final Fantasy VII or even Final Fantasy and find it enjoyable and understandable. A majority of this review examines a story that has little to do with the game and exists entirely within the film. Fans have as much difficulty decoding the superficial geostigma-Jenova-Sephiroth story as non-fans do, and anyone can understand the parallel story about a guy struggling with his past. In fact, many Final Fantasy VII fans complain that the movie doesn’t contain enough fan service. The film spends more time on Denzel and Kadaj, characters that don’t exist in the game, than it does on the game’s playable characters. Additionally, the short battle with Sephiroth ends rather suddenly for a film that supposedly exists solely to create an excuse for the fight to happen. The film also doesn’t add anything new to the Final Fantasy VII universe. It opens with the message, “To those who loved this world, and knew friendly company therein: this Reunion is for you,” but it simultaneously provides evidence that it’s not for fans only.

Advent Children seems more like a film that uses Final Fantasy VII as a medium to tell a story than a fan service film. It has elements that only fans can understand, but that doesn’t mean that everything else is incomprehensible. We don’t need Barret, Yuffie, and Cid’s backstory to understand that they’re Cloud’s friends and helped save the world two years ago, for example. The backstories clearly exist because these characters have distinguishing personalities. The movie simply chooses not to present the stories of its side characters and peripheral details like a lot of other movies choose to do.

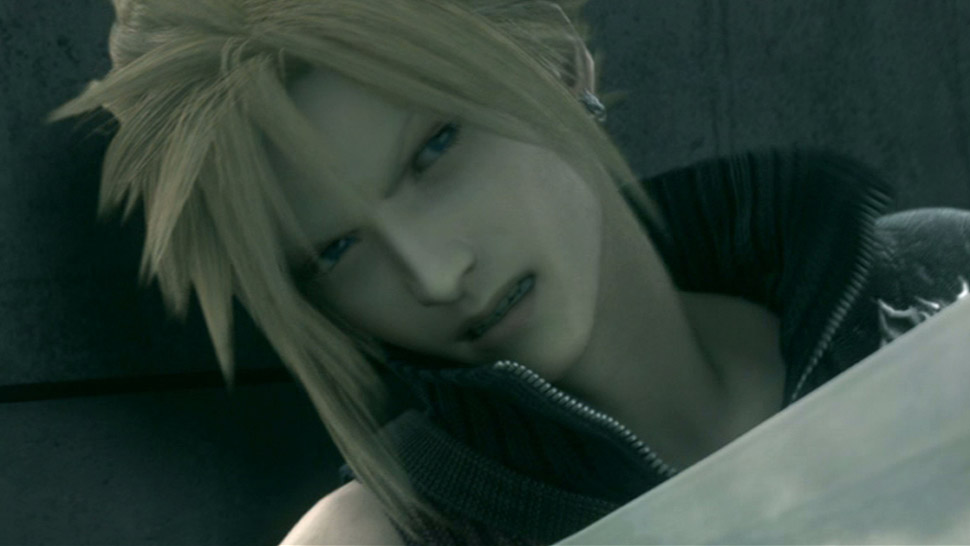

“Fan service” can also mean gratuitous sex and violence. Advent Children features a cast of male characters that fit the pretty, sexy man stereotype found in many Japanese anime and relentless, sword-swinging action. When an anime doesn’t have anything interesting to say, it can resort to large-breasted women and effeminate men with partially open jackets and large swords to find an audience. Movies with these elements, however, can still have great stories and ideas to share. Hollywood has many pretty faces, but we don’t condemn all its movies as bad simply because the actors aren’t hideous. Fight Club isn’t critically acclaimed because it features Brad Pitt and two hours of men punching each other in the face. It tells an excellent story with an interesting commentary about life. Advent Children’s creators made the characters aesthetically pleasing (Who wants to look at butt ugly artwork?) but not radically different from their basic designs in the game. The film has a story and messages applicable to real life told through the action, pretty men, and Final Fantasy VII elements at its surface.

Reviewers have also classified Advent Children as photorealistic despite no one in the film looking like a real person. In the wake of Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within and The Polar Express, critics labeled Advent Children as yet another attempt at photorealism with a poor story. Unsurprisingly, critics complained that it didn’t look realistic enough. Characters don’t follow the real-world laws of physics, they don’t bleed, and the movie never tricks the audience into thinking that it’s live-action. No evidence suggests that Advent Children is or ever was meant to be photorealistic. The anime-influenced characters look too perfect and alien to be real. Like cutscenes in Final Fantasy games, Advent Children only presents the illusion of realism. The creators even state in The Making Of featurette that they didn’t want to make a photorealistic film. As co-director Takeshi Nozue says, “If it looked too real, then we might as well shoot it live.” Ignoring the laws of physics and not showing blood are stylistic and thematic choices that don’t affect the quality of the story. If we don’t expect Pixar films or video games to trick us into thinking that we’re watching real people, then we shouldn’t hold Advent Children to this standard either.

Finally, critics make claims about Advent Children simply because of its association with a video game. Video game movies generally don’t have great stories, but they can break this stereotype. Reviewers describe Advent Children as one long cutscene, which suggests that it doesn’t contain enough information on its own to tell a story. Everything about its story, its themes, and its characters except a few details in this analysis comes from the movie. Other reviewers have called Advent Children a series of cutscenes. This description just applies a video game term, cutscenes, to the elements that make up all movies, scenes. This metaphor doesn’t contain any information about whether the movie is good or bad. Some argue that the film can’t engage the audience because it’s not a video game. Depending on the gamer, cutscenes in games are either a reward or an annoyance, and Advent Children shows an hour and a half of beautiful visuals without requiring the player/viewer to do anything. It’s true, movies don’t reward strategic button pressing. The reward lies in finding meaning in their visuals and audio.

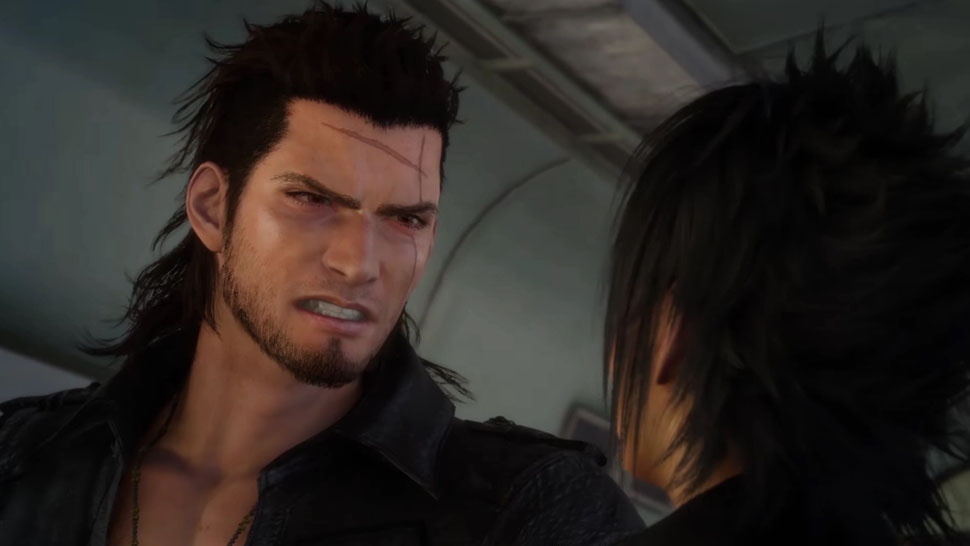

Advent Children defies all these descriptions and criticisms because it’s unlike anything ever created. Beowulf defines technology porn, a photorealistic spectacle brimming with graphic sex, gore, and violence. A series of cutscenes accurately describes .hack//G.U. Trilogy, a film obviously missing crucial explanation and character development that would usually occur during gameplay. Similarly, a long cutscene describes Kingsglaive: Final Fantasy XV, a film that doesn’t even explain what problem its characters must solve because it’s in the game. Tekken: Blood Vengeance, a film that contains a ridiculous plot that ties together apparently pointless fight scenes between characters from the game, is one type of fan service film. .hack//Beyond the World, a film that loses itself in .hack lore without explaining why it matters to the protagonist, demonstrates another. Elysium (2003) shows what terrible but brief dialog combined with a terrible story looks like. Want to know what Advent Children would sound like had it explained everything in excruciating detail? Watch Ark (2005). Kaena: The Prophecy makes a sincere but novice attempt at using a video game world to tell a story, what Advent Children near perfects.

While Advent Children takes inspiration from Japanese anime and live-action films, it uses CGI to its full potential to tell a story in its own way. It doesn’t use cell shading to mimic hand-drawn 2D animation like Appleseed, nor does it try to mimic live-action like The Polar Express. It avoids the uncanny valley without severely deforming its heroes like A Christmas Carol does. It retains the illusion of realism and humanity even when the characters defy the laws of physics. It entertains without resorting to excessive sex or violence like Starship Troopers: Invasion or Sausage Party do. It’s an art film and drama disguised as an action movie. It tells a thoughtful and universal story through elements from a video game. It uses CGI’s strengths to create choreography, characters, environments, and camera work that would be extremely difficult to recreate in any other medium, but it doesn’t discard basic filmmaking and narrative techniques. It creates a visual spectacle but never forgets that first and foremost it must tell a story. In a fledgling art form that struggles to tell any kind of meaningful story outside of children’s entertainment, Advent Children is one of the most important CGI movies ever made.

Even with its uniqueness, Advent Children can still be judged and analyzed as a movie. It contains a story with characters, conflicts, and themes. It has spectacular battles as an action movie should, but it also conveys a meaningful narrative through its mise-en-scène both inside and outside the action scenes. While it has flaws, they don’t immediately discredit the film as a pointless visual spectacle.

Advent Children has never been treated as a work of art or even as a movie though. It’s viewed through the lens of fan service, visual spectacle, and video game bonus material. It’s judged as a bad movie because it doesn’t contain enough fan service, isn’t realistic enough, and is based on a video game. None of these complaints address whether Advent Children tells a thoughtful story that connects with viewers, uses filmmaking techniques effectively to convey meaning, or doesn’t do either. And that’s a shame. From what I’ve seen, Advent Children makes the best use of known filmmaking, storytelling, and animation techniques to tell a fantastic, mature, and human story through CGI out of all films in its class.

That’s why people love this movie. That’s why it never fails to make me smile. Now I no longer ask, “Why do I like Advent Children?” Now I ask, “Why shouldn’t I like it?” I hope you’ll ask these questions, too. The film could mean something different to you as a Final Fantasy VII fan or as a person than it does to me. If you don’t like Advent Children, I hope you, too, will ask yourself why. Is it genuinely a terrible movie, or does it just disappoint some Final Fantasy VII fans and moviegoers? And, of course, if you’ve never seen it, watch it. Playing the game first is optional. Advent Children isn’t perfect, but it’s worthy of criticism and analysis. It has so much to say, and filmmakers have so much to learn from it.

What does Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children mean to you?